Do EBIT and EBITDA give a better indication of the true operational performance of the business? asks Richard Arnott

In continuation of our series attempting to demystify finance, we will discuss a term or terms that will be heard frequently for those of you who work at for-profit organisations.

Many of you will have sat through operational or finance meetings and will have heard those attending fixating on something called EBIT and EBITDA. You have always intended to ask what it means, but by the time the meeting has finished and you have written up the Minutes or Actions and distributed them to everyone, something else has landed in your inbox or the Office Interrupter has appeared at your desk for one of their many daily “wee chats.”

Meaning

EBIT means “Earnings Before Interest and Taxation.”

EBITDA means “Earnings Before Interest and Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation.”

Both are measures of profitability; however, they look at profits in different ways to give what some people claim to be a truer picture of operating profit.

Measuring Profit

Most of you will have heard of “gross profit” and “net profit.”

Gross profit

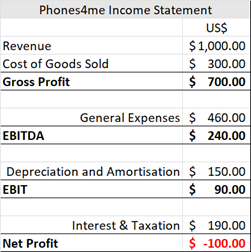

Gross profit is the measure of income received less the “cost of goods sold.” The cost of goods sold is the direct cost of the goods or services that your operation provides. Take the example of a cell phone retailer (let’s call them Phones4Me). Phones4Me buys cell phones from their supplier at $300 per unit and sells them to the public at $1,000 per unit.

The gross profit is revenue – cost of goods sold, or in this case $1,000 – $300 = $700.

Net profit

Net profit is the measure of revenues received less all costs incurred, not just the cost of the goods sold. In our example,let us assume that Phones4Me has additional costs of $800 to account for general expenses such as staff salaries, electricity, etc., plus Interest on loans taken out, plus Taxation on sales and profit, plus an allowance for Depreciation and Amortisation costs (we will look at Depreciation and Amortisation later in this article).

The net profit is revenue – cost of goods sold – expenses, or in this case $1,000 – $300 – $800 = -$100.

Phones4Me is reporting a net loss of $100.

Now let’s say that the total of all additional costs was $800, made up of:

- Interest ($100)

- Taxation ($90)

- Depreciation & Amortisation ($150)

- General Expenses ($460)

Another way to look at the income or profit & loss statement would be:

The EBIT calculation adds interest and depreciation back into the equation, so EBIT would equal net profit of -$100 + interest ($100) + taxation ($90) = $90 EBIT. This is now a positive figure.

The EBITDA calculation adds the allowance of depreciation and amortisation back into the equation, so EBITDA would equal EBIT ($90) + depreciation & amortisation ($150) = $240 EBITDA (another positive figure and higher than EBIT!).

So, your executive is now delighted that EBIT is positive and EBITDA is also positive and higher than EBIT. Backs are being slapped and bonusses are being discussed due to their great performance.

But why? You made a loss, didn’t you?

Definitions

Before we progress further, we need to clarify the definitions being used.

Interest

Interest is the amount that the organisation is paying to finance any debt. It is the same as the interest you would pay on an automobile loan or a mortgage.

Taxation

Taxation is simply the amount that the organisation owes to the local tax authorities (again, similar to what you pay on your salary or other incomes).

Depreciation and amortisation

Depreciation and amortisation is an accounting practice that spreads the cost of capital equipment or other one-off expenses over an agreed period (in theory over the useful life of the asset). For example, if an organisation paid $900,000 for a new piece of machinery and that piece of machinery had an estimated useful life of 10 years, the organisation may decide not to hit the first-year profit & loss with the full $900,000. It may choose to spread this over the next 10 years, deducting a nominal $90,000 per year. For tangible assets, like a piece of equipment, we use the term “depreciation”; for intangible assets, like a patent or goodwill, we use the term “amortisation”. Otherwise, they are treated the same.

So Why the Delight?

Operational profit

The reason that some executives fixate on EBIT and EBITDA is that they believe it gives a better indication of the true operational performance of the business, excluding factors that are outside the control of management. For example, management do not dictate the interest rate being paid nor do they set the level of taxation, so excluding these in the EBIT calculation seems to be a fairer measure, especially if performance is being compared across states or countries where different interest rates and taxation regimes may exist. The argument is that it enables pure operational performance to be compared between similar operations.

Secondly, nominal costs such as depreciation of an asset could be based on a decision taken five years previously by a totally different management team. The argument goes that the current operational management team should not have their performance measured based on previous management’s decisions, or indeed, mistakes. Hence, removing depreciation and amortisation costs as well as interest and taxation from the equation will give an even fairer measure of current performance. Hence EBITDA.

A further argument is that certain costs such as interest payments or depreciation will not last forever. For example, the company loan may be getting paid off in two years’ time, or the “useful life” period for a fixed asset is coming to an end, so in two years’ time there will be no interest or depreciation charges on the books. So why not recognise that now? This is the argument.

A good analogy is to think of yourself. Imagine that for this year and for the past 10 years, your annual expenses have been greater than your income. You are paying off a mortgage with a high interest rate and also a capital repayment, and you live in a state / country with high taxation. However, next year your mortgage is going to be paid off and you are moving to Costa Rica. Your salary will remain the same.

Today you might look in horror at your bank statement each month, but deep down you know that by this time next year, you are going to be financially flush. No more mortgage, no interest payments and lower tax bills, but the same income.

This is similar to what your executive is thinking. Despite the interest and depreciation costs today, they know, deep down, that the business is operationally profitable and once these extraneous costs are removed, then net profits will increase.

Bearing in mind that EBITDA is always higher than EBIT and EBIT is always higher than net profit, what would you rather have your bonus based on?

Danger

Not everyone agrees with using EBIT or EBITDA in this way. Many claim it gives organisations a false sense of security and results in bonus payments that the organisation cannot afford. Probably the most famous opponent is Warren Buffett, who thinks that using EBITDA is like the tooth fairy paying for capital expenditure. Buffett says that organisations will always borrow, so they’ll always be paying interest (just for different reasons), and that successful organisations will always be investing in new capital equipment or intangible assets, so depreciation and amortisation will always be a factor.

Personally, I tend toward Buffett’s thinking. I have seen too many businesses where management have convinced themselves that due to positive EBIT and EBITDA figures, as opposed to a net loss, they are operationally sound and everyone deserves a bonus. I have seen organisations fold for not recognising this.

So next time your executives and colleagues start fixating on EBIT and EBITDA, ask yourself if their assumptions are correct. Are interest payments going to fall in the future? Is taxation abnormally high compared to other states / countries? Will there never be the same capital expenditure in the future as there has been historically?

The brave amongst you might also challenge your executive. Your executive may just be in what I call “the EBITDA groove.” It is the way they always measure performance; it was the way it was measured when they joined, and it has never been changed nor challenged.

Good luck!