Psychological safety is about establishing a people-centric culture explains Jason Liem

I have written quite extensively on how our brains deal with uncertainty. It is even more relevant now than anything in our recent, collective memories. We have concerns about physical safety, financial health and job security. We don’t know if the current state of affairs will last 12, 18, 24 months or longer.

Trauma therapists know well enough that what follows a physical ordeal is a psychological one. Trauma is about undergoing a distressful or disturbing experience. COVID-19 has created a collective trauma.

Physical safety has been and is the major focus. Working from home and social distancing are strategies employed to reduce physical harm. Currently, there is very little focus on psychological well-being.

From my perspective this detrimental imbalance prompts a vital question. Do we come out of this pandemic with post-traumatic stress or with post-traumatic growth?

The answer is obviously the latter. Psychological safety is an essential element if we are going to arrive at this outcome. Psychological safety is as relevant now as it has ever been.

The Managing Self

It takes between 8 to 40 thousandths of a second for our brains to register the emotions of others, and even less time for us to feel what they are feeling. We have all experienced how the moods of another can influence our emotional state. The term for this is emotional contagion. The effect of emotional contagion is amplified if the other person sits in a position of authority – such as a parent, a manager or coach.

If you happen to occupy such a position, it is even more important to be able to manage your thoughts and feelings. Of course, this is easier said than done. This can be a real challenge when we are in a state of distress. When the natural instinct is self-preservation – focusing on the me and losing sight of the we. Mental and emotional agility is the ability to override this evolutionary programming.

It’s essential that we take a moment to observe, reflect and then choose to act. We must remind ourselves to move from the me and to also include the we. This is a fundamental step to establish psychological safety. We need to be genuinely curious about how people are coping and what challenges they are facing.

Mental and emotional agility also includes modelling healthy behaviours. This means taking care of ourselves by taking breaks and getting enough sleep. The healthy work standards we set for ourselves will set the bar for others to follow.

What is the Social Brain?

We all have physical needs that must be met. We require food, water, and shelter. At the same time, we have natural psychological needs. We need to feel we belong, that life has meaning and purpose. We need to feel that people see and value us. We need to feel we have a future that makes sense.

Our brains evolved to thrive in a tribe. When our relationships are strong and functional, we feel appreciated, valued, respected, acknowledged, and certain. The term for these positive emotions linked to relationship is social reward.

The opposite is true when our key relationships are dysfunctional. We feel disengaged, disconnected and disheartened in those relations. We can experience negative emotions – such as feeling ignored, unappreciated, and disrespected. In other words, we experience social pain.

The Insula

The insula is the structure that affords us the ability to think about, feel and to anticipate pain. It’s functioning also allows us to experience the beating of our heart, the ache of sore muscles, the rise and fall of our breath and to feel hunger and thirst.

This awareness of your inner body sensations is called interoceptive awareness. This internal perception to our ongoing experience is an important element when discussing psychological safety. Let me ask you a few questions to illustrate this point:

How does it feel to be given the cold-shoulder?

What situations awaken your empathy?

How do you react when you see disgust on someone’s face?

The ability to experience any of these situations also requires the functioning of the insula. It is what allows us to feel the positive and negative emotions linked to relationships – to experience social reward and social pain.

Social Pain and Physical Pain

Our brains have two different and dedicated pain circuits – one for social pain and the other for physical pain. Although distinct, evolution has seen fit to link them together.

This is understandable when you consider our ancient ancestors had a greater chance of living through the day if they knew they were an integral part of a group. The tribe hunted together, shared resources and defended each other. In essence, their physical survival was, in a large part, contingent on the health of their social connections.

As contemporary human beings we still have this primal wiring. So, when our social pain network gets triggered so does our physical pain network. This means when we experience rejection or unfairness, we actually experience physical pain. The pain motivates us to relieve the pain by improving our social bonds.

Here is an interesting fact. When we experience a mild discomfort – like a headache – we can take an aspirin to relieve the pain. This same aspirin can also temporarily dull the social pain of feeling ignored or rejected.

Temporary is the operative word. Once the effects of the aspirin wear off the headache will return if the underlying reasons for the headache are not treated (i.e. stiff shoulders, dehydration, lack of sleep). This is also true for social pain.

The Amygdala

The amygdala is the part of the brain responsible for tracking members of our group. It monitors the quality of the relationship by tuning into their intentions, mannerisms, inflections, body language and a number of other social signals.

The amygdala monitors for any deviations from the norms of that relationship. Its singular mission – other than detecting danger – is to ensure we stay tightly knitted to our tribe.

The intensity of the amygdala’s monitoring increases when it involves our relationships to authority figures in our lives (i.e. managers, coaches, teachers and parents), since their decisions or communications can have a more significant impact on us.

The 3 Most Important Social-Emotional Values

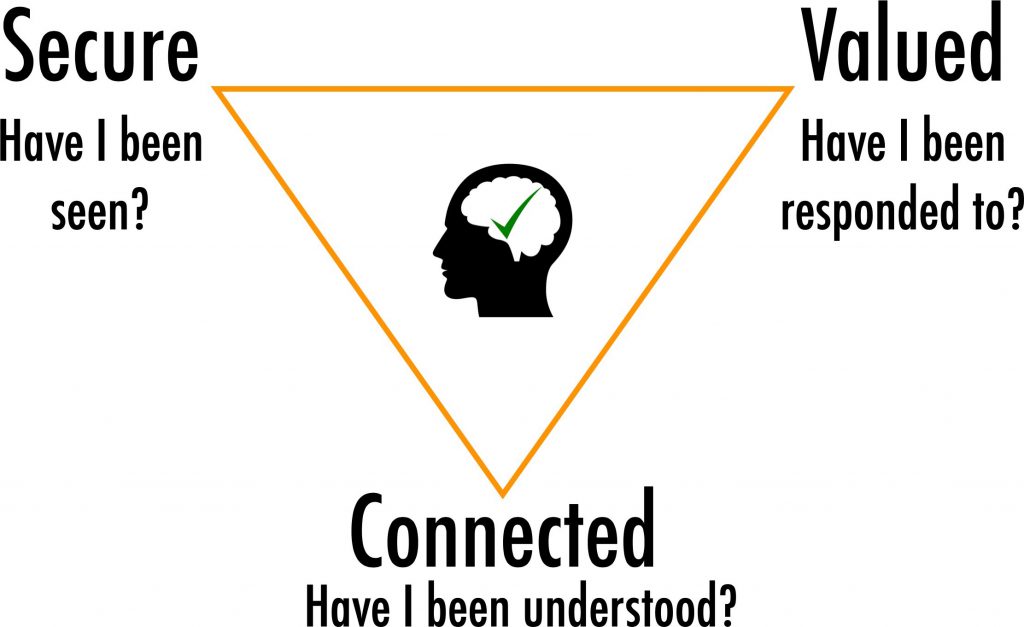

Every human being has the inherent need to feel secure, connected and valued to people who are significant in their lives. It could be their family, a group of friends, a team or an organisation. These social-emotional values translate into three questions:

SECURE – Have I been seen?

CONNECTED – Have I been understood?

VALUED – Have I been responded to?

In a sense, these values are the amygdala’s watchdog. If we answer yes to each of these questions, then we can say, “I’m seen, I’m understood, and I’m valued!” We experience psychological safety and remain in a reflective mindset.

In this state of mind, we are more engaged and motivated. We focus on both the me and the we. We actively engage in communication, collaboration and cooperation.

If we answer No to any one of the three questions then the amygdala’s watch-dog growls and barks. It translates a strain in the relationship as a threat to our life and limb. We don’t feel psychological safety and we hurtle headlong into a reactive mindset.

Our behaviour reflects this defensive mindset. We become guarded, overly protective, and we shut out others. The me becomes the only focus as we get more wrapped up in self-preservation.

The Tools

Connection Signals are the Key

Creating psychological safety is not a single, one-time message that we are safe in this group. Human beings are emotional creatures who require continual signalling that everything is all right. This goes straight to the heart of building healthy relationships. It is not a single big investment. Rather it is many small investments over a long period of time that communicates, “I see you. I hear you. You are valued.”

This is not to say teams who have a strong sense of psychological safety do not have problems and conflicts. Of course they do. The difference is that these teams have established well-defined rules of engagement. They feel safe to confront ideas and question decisions. They feel free to voice opinions and share feedback in all directions.

The questions found below are a great way of sending connection signals to a team. When I work with teams I encourage them to include these questions into their weekly huddles. It is a strong tool for communicating and creating inclusiveness.

What are we doing well?

What can we do to improve together?

Where did we struggle with motivation?

Where did we thrive?

How are we doing taking care of each other?

One to One Meetings

One of the best forums to establish psychological safety is the one-to-one meeting. It is an anticipated conversation where manager and employee can connect and communicate. In this space individuals feel safe to discuss their issues and concerns.

One-to-ones help a manager to check the pulse of their team and to ensure there is alignment. It prevents larger issues from festering. It’s an ideal space for coaching, sharing feedback and even venting.

A typical session tends to be approximately 30 minutes in length. They are usually spaced one to two weeks apart with each member of the team. The flexibility of a one-to-one means they don’t have to always be held in a meeting room. You can combine a one-to-one as a walk-and-talk or as a sit-down at a cafe.

A good way of opening a one-to-one is by asking open-ended questions. This allows the most important and top-of-mind topics to surface.

How are you feeling?

What is on your mind?

What are you most excited about?

What are you most concerned about?

What is of equal importance to asking good questions is listening reflectively to what is being said. Keeping a focus on both of these skills is key to making sure team members feel safe, connected and valued.

Reflective Listening

Reflective listening has two parts. The first is the signals acknowledging we are following the other person’s train of thought. This could be a nod of the head or simple worded phrases. The second part is reflecting back with questions and insights. It’s about helping people to put words to thoughts and to explore their thinking.

With that said, it is not about making suggestions or offering solutions. It’s getting people to expand on their ideas and to come up with different permutations of their initial thoughts. It is then about helping them to translate those ideas into concrete actions.

Shared Sense of Purpose

A shared sense of purpose is essential if people are to feel connected, engaged and open to ideas. It communicates to team members that we have a common and shared future – an essential ingredient to psychological safety.

Values lie at the heart of purpose. Values provide a guide and a philosophy to the things we do. For example, we may value a sense of contribution, or service to others, or being creative or any number of things.

Values are not a checklist that we cross off. There is no single thing you can do or achievement you can reach that can forever fulfil a value. A sense of purpose is something you move towards – a direction. It is not a distinct destination, which is what goals are.

Goals

Goals are tasks and milestones we aim to achieve. This might be completing a project, finishing a course, or getting promoted. They are measurable and have an endpoint.

Goals for the sake of goals are useless. Goals not connected to a purpose seem vacuous and superficial. They are a detriment to psychological safety.

Goals linked to a shared purpose – to a set of shared core values – broadcast both a destination and a direction. This connection communicates to team members that we have a common and shared future. Let me illustrate this with an example.

The Review and Learn Process

A team I recently worked with defined a part of their shared purpose as: We are a team that learns from mistakes. They translated this into an actionable procedure they termed a review and learn process (RLP). At the conclusion of every project, they conduct a RLP that includes the following five questions:

What was our expected outcome?

What was our actual outcome?

What caused our outcome?

What will we repeat the next time?

What will we do differently, change or eliminate next time?

Connecting purpose, goals and behaviour communicates that a team has a shared future. It sets the priorities and expectations for the team, so that knowing what to do and why gives clarity in times of uncertainty. This, in turn, cements the social-emotional values and deepens a sense of psychological safety.

In Conclusion

Psychological safety is about establishing a people-centric culture, where the focus is on helping people feel secure, connected, and valued. Further, it is about instilling a sense of common purpose and shared future.

The dividends are well worth the effort. People are more empathetic, question their biases, learn, explore and grow. It has the additional effect of encouraging people to speak their minds, share feedback and build bridges within and across teams. In times of change, employees feel safe to innovate, create, collaborate and cooperate. From my experience, there are only upsides to creating a culture where people feel secure, connected and valued.